Back in the summer of 2014 we sat down with Sarah Smith from Institute For The Future as part of her research for The Future of Food in 20 Objects. We finally had a chance to transcribe the interview and even though it is off the cuff, and conversational, we thought that included a good summary of our first four years worth of research.

NOTE: Some sections of the interview have been edited for clarity or accuracy.

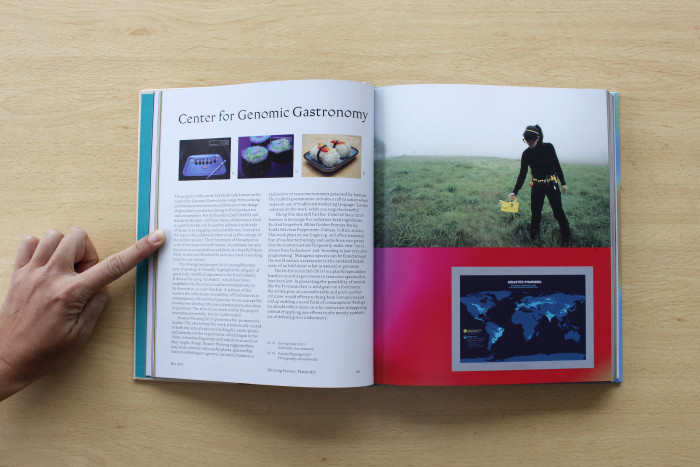

SARAH: I would love to start with you description of the Center For Genomic Gastronomy and your mission.

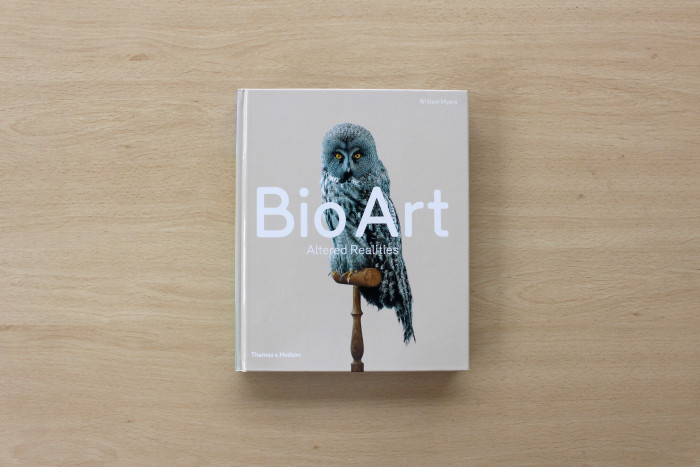

CGG: Our official description is “An artist-led think tank that examines the biotechnologies and biodiversity of human food systems,” but we’ve been working on a new way of defining Genomic Gastronomy in the last year, which is “the study of organisms and environments manipulated by human food culture.”

We were really interested in looking at food from the prospective of biology and ecology. The title “Genomic Gastronomy” came from a play on molecular gastronomy, which was (and is still) very popular. [Molecular gastronomy] was all about chemistry and a reductive approach to food: how do we understand the base chemical elements of food and build up a narrative or event from these chemical constituents?

When we started in 2010, there was a big transition in the high-end cuisine world from [restaurants like] El Bulli and Fat Duck to NOMA and the Scandinavian approach. We started joking that NOMA was really just a restaurant that was doing “Genomic Gastronomy” and that they stole our idea. [It was] a bit facetiously because we thought well, we are artists and don’t have a big relationship with the restaurant or food world. But then, about two years ago, we were contacted by Nordic Food Lab (NOMA’s R&D restaurant) and we went over and had dinner with them. It actually turns out that there IS a lot of crossover, which is really fascinating. They are interested in terroir and time and place in [a given] region of the world. But they also spend a lot of time looking at the different cultivars of plants, and different sub-species of fish and ecosystems of fisheries. While we’re trying to push ideas from an artistic angle, looking at biotech and ecology, high end cuisine is already heading in this direction, so there was an interesting confluence we hadn’t predicted.

S: So neither of you had any food system background before this? You come at it from the art perspective?

CGG: When we met in 2010, Cat had been working on an ice cream van that attempted to make it snow ice cream, and [Zack] was doing food research with art students in Bangalore, India.

ZACK: I had been really interested in what was happening with biotechnology, and I was seeing a huge lack of criticality. On the one hand there was industry hype, and on the other hand popular resistance to GMO, but there seemed to be very hardened cultural positions. We thought artists had a role to play in challenging the norms and metaphors that were playing out. Many of the [pre-existing] metaphors used within the biotech literature and field were about engineering (see: BioBricks and IGEM). These metaphors really glossed over the ways life is actually quite different from code. That was a huge inspiration, so we started [asking], could we use food or gastronomy as a lens to challenge these norms of biotech?

Since then we’ve really branched out because [we discovered that] biotechnology in itself is really a poor metaphor for the interaction of humans with other life forms, mediated by tools. Now, we’ve gone way beyond that initial idea of food and biotechnology.

S: [To discuss] that idea of driving metaphors of our current food system, for example the industrial metaphor as a dominant one, [has there been a] shift from industrial models to information age [models]? What does that look like in the food system to you?

CGG: There’s an assumption that we go from an industrial to a post-industrial information economy, but we’re seeing another trend as well, which is the craft economy— or a desire for people to relate to their local ecosystem services or their region. It doesn’t have to be totally separate from the information economy, but there does seem to be a schism.

There is also a fundamental materiality to food that you can’t really digitize, no matter how much people try.

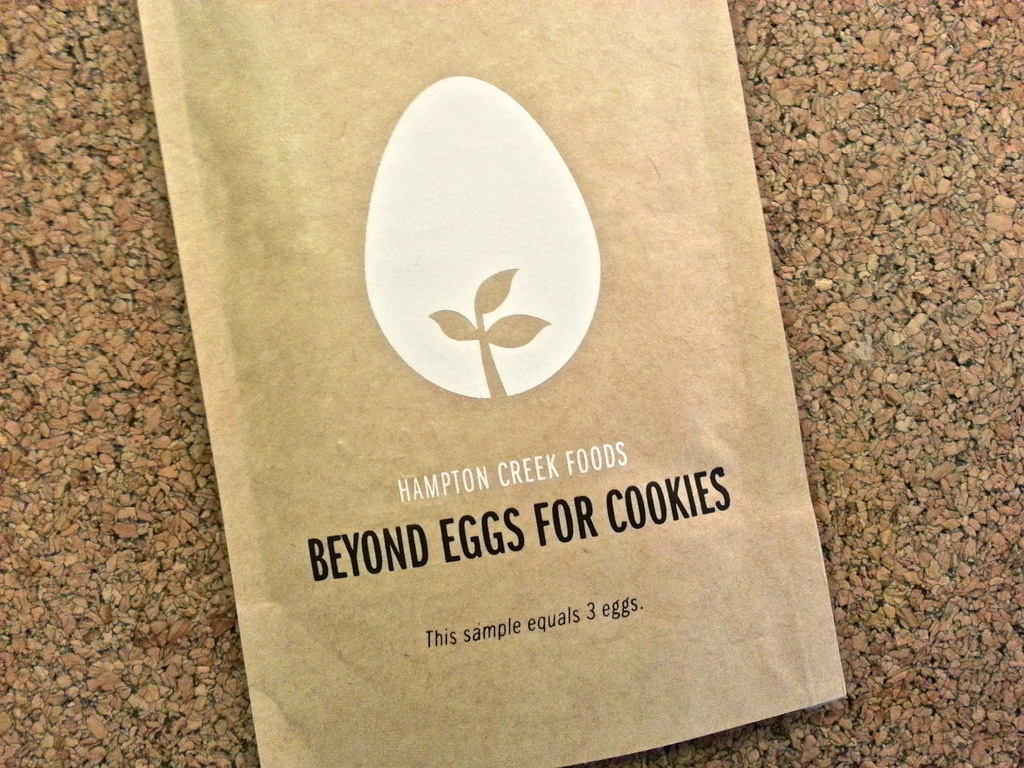

Beyond Eggs & Soylent

S: Beyond Eggs is a good example [of a] distribution model where you would break things down into small parts and distribute it through a resilient network.

Centgg: We do spend a lot of time thinking about technology, but I think it’s not an either/or, it’s a both/and situation—like contemporary architecture that tries to be sustainable, but doesn’t just look backwards towards regional materials and methods, but also uses high-performance materials. I think we’ll see really interesting food cultures take these hyper-efficient, lets say, industrial materials like Beyond Eggs, but also combine that with hand-foraged herbs from a new walkable forest that is planted.

Right now I think there is a really awesome opportunity to bring those two worlds together. We have a lot of reactionary, conservative food groups (for example, [groups who think we] should only make sourdough the way it was made 500 years ago), and we also have this food start up movement that wants to “disrupt” everything. Those are both less interesting than if they were combined. I think that’s where we get really excited.

The information technology space [enables lots of] information about organisms, ingredients and techniques to go around the globe really fast. We’re particularly interested in (and [currently] exploring through our Food Phreaking project) the bringing together of some of the ideas, ethics, values, and metaphors from the open source and open culture movements to food technology. [Right now], a lot of well funded food technology is following the privatized model.

Soylent is interesting because even though we think it’s a ridiculous project, they do have the sort of open source community side, and they are trying to make an open platform. But from the prospective of nutrition and other things it follows these absurd, 1950s, pill food ideas.

CGG: A Scottish scientist we’ve been working with who studies phytochemicals and micronutrients, argues that we don’t know enough about what [humans] need to be healthy. There’s no way you could be so reductive with a product [like Soylent] and be healthy.

And even from her perspective, focussing on the nutrition, why would you want to [be so reductive]? I think that’s what a lot of people are reacting against: we don’t want just industrialized food.

CGG: The application of design and design thinking to food is actually super scary because it presumes that there is always a need for new “products” and tends to define innovation in terms of efficiency, fungibility and profit. Products and innovation aren’t in themselves bad things, but [design thinking in food] has actually kind of been a failure as practiced in the market. Some very interesting design thinking projects that were community oriented have more promise…

I think looking towards the future, code and disruptive design, and the tech industry in the Bay Area, are terrible metaphors for what we should be doing with food. We need metaphors that are much more interesting and appropriate to life than “disruptive innovation” , and I am not sure they exist yet.

Biohacking’s an interesting [direction], but it’s maybe more interesting in Europe where there’s more consideration of how to combine it with tradition, or how to maintain it in a context that is political and not just profit maximizing.

Culinary Breeding Network

IFTF: So, in that context of the ethos of an open source movement, are there specific technologies or even efforts that you’ve seen that really excite you or are interesting application of open source technology with food?

CGG: Open source seeds [have been in the news recently]. Plant scientists are concerned about the consolidation of seeds and the privatization of seeds. Their research is being affected by large companies patenting certain traits that they’ve been working with for twenty years. So, while it was a much more open system in the past, now it’s closing… It is very fascinating because it brings up so many interesting legal questions and the [scientists] who are doing this have no financial weight [compared to the giant corporations], so basically if it did become a legal issue there would be no way of [funding their side].

The Culinary Breeding Network is a fascinating organization that we are hoping to learn more about.

CGG: Two colleagues of ours that are doing really great work are:

Hackteria (a DIY bio group run by Marc Dusseiller). They do a lot of workshops and pulling together methodologies and tools, and making inexpensive hardware and methods for DIY biology. There’s often a food element because that’s what brings people in. But what I think is really important about them is that they are really serious about the open source aspect of everything they do, and you already see a lot of DIY bio communities becoming more proprietary and less open, so they are a counter example of that.

Daily Dump in Bangalore, India is more about dealing with food waste side. Poonam Bir Kasturi has [created] an open source business platform for at home processing of food scraps. It’s a really interesting model for an open source business. She started making a few of these local businesses, but [now anyone] can clone the whole business and [she] provides all the resources to do that.

CGG: There’s always a tension between fungibility and efficiency versus resilience, and I think that’s the problem that large organizations have in this space. It’s that they are thinking primarily in terms of efficiency and economies of scale, but when it comes to food and integrating back into sustainable services and ecosystems, we may not want that, we may actually want diversity, sovreignty and resiliency. It’s not an either / or, but efficiency still seems to be at the center of most policy and market conversations, and advocates of resilient de-centralized systems are mocked in the mainstream.

We may want plants that ARE’NT fungible, that we sort of have to keep near where they are grown that don’t make sense to export whether it be nationally or internationally, increasing local food sovereignty. So that’s a huge tension.

The Climate Cooperation is a really interesting company. In a way, it’s a shame that they were acquired by Monsanto because it casts a shadow and people are going to be skeptical now, and using the goal of efficiency, and armed with cheap code and cheap data, the costs could be so low that lots of different kinds of farmers could use it, not just intensive industrial farmer. These kinds of things could work at multiple scales, but they may not just because the money’s not there, but that maybe is the promise of digital technology. They can scale across everything from a one acre urban farm to 5,000 acres.

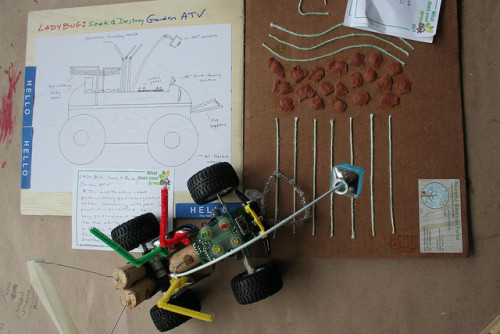

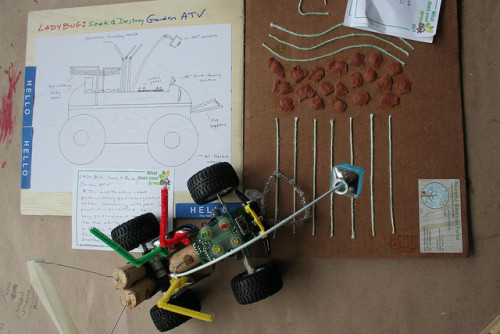

Carl DiSalvo (with his GrowBot Garden) has been doing a lot of good research on how agricultural technology could be applied at different scales, not just industrial farming, but also urban farming or permaculture. For example, could we imagine agricultural products for permaculture? This goes back to my earlier point: there doesn’t have to be a separation between tech and nature. Something like robots for permaculture, what would that look like? And that’s a way more interesting metaphor than the industrial metaphor or the reactionary response of robots don’t belong in farming.

GrowBot Garden

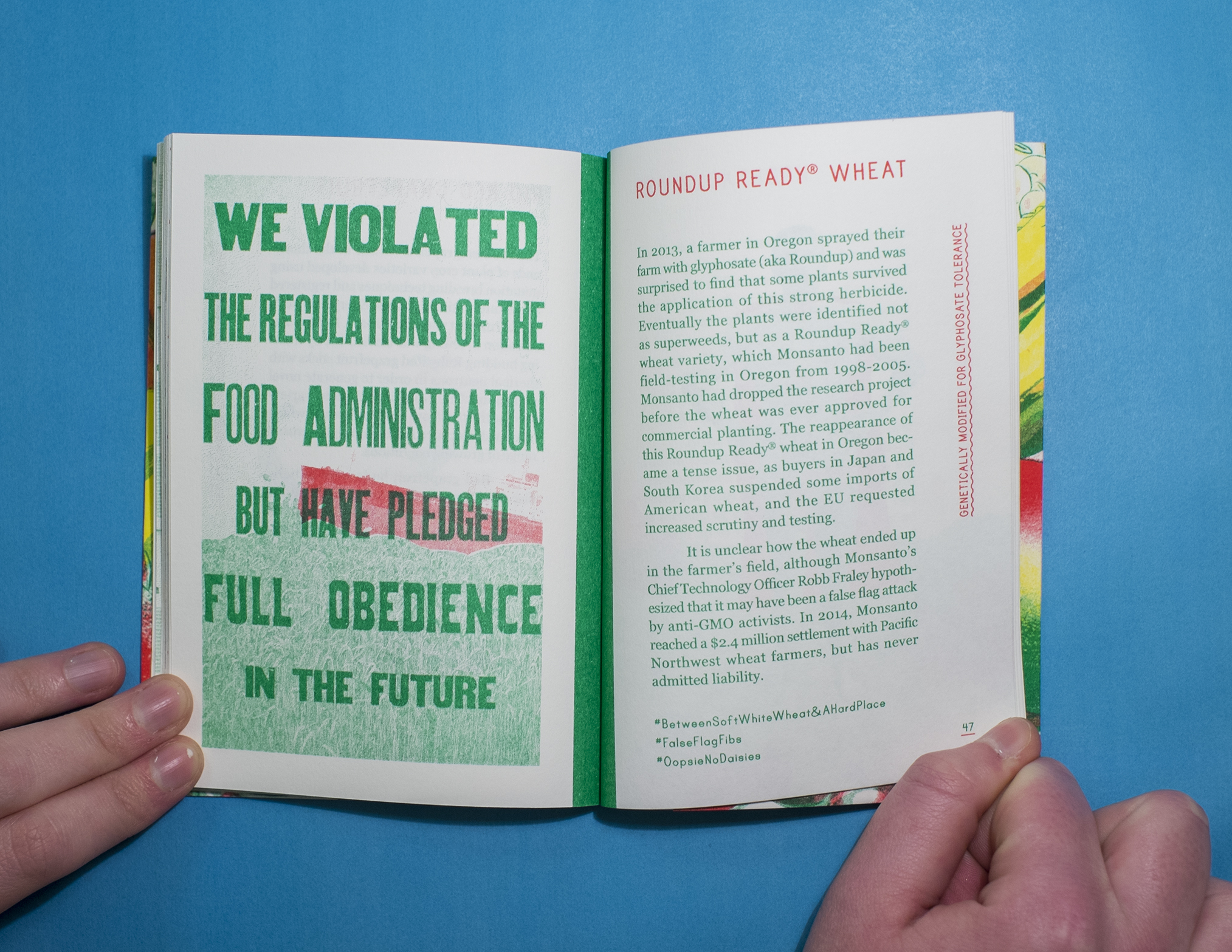

S: I want to go back to the whole topic of groups like Monsonto casting a bad light on genetic modification and people’s fear of genetically modified food. What are you seeing in terms of a cultural shift in being more open to biohacking and will become accepted?

CGG: I don’t think there’s been a shift in Europe. In the US, there’s a lot less criticality. When things enter the supermarket, people seem ready to adopt these new technologies, which is cool—it’s one of the things I love about America, but Monsanto’s done such a bad job in conducting itself [and] in public relations, that even in the US, it’s going to be a long time before people are openly and actively desiring different kinds of transgenic organisms to be part of the food system.

S: Do you think that transparency or people’s personal experience and getting to do it themselves [is important]?

CGG: [There are techniques] for making these technologies more acceptable to the public, but I don’t think we presume that these technologies or techniques are good at a system-wide scale. There’s nothing about making corn more efficient that we believe is really helpful because that falls again into this industrial paradigm. All these biotech techniques are very exciting, if they are used for things that are desirable by individual human beings or communities. There’s nothing particularly interesting about making corn more efficient because it is again that top-down industrialized vision. What we dream about is how to use biotech to make something like a tomato that is more flavorful. Imagine if there was a breeding network devoted to using any breeding technique possible to make the most flavourful and untransportable tomatoes possible. How could you imagine having the most ridiculously over-engineered plant that could only exist in this one square mile, so that it couldn’t be exported, and it would just rot as soon as it left a very small micro-climate? To take it out of the fungible, industrial system. And those are very interesting provocations, but the problem is right now, all the metaphase and funding is coming from private industry, and even academic research is trying to solve problems, and maybe being too narrow with what we could dream of for these technologies.

S: Do you think that breeding for something like draught resistance is just not addressing the real problem?

CGG: You want to improve and perfect crops for different situations, so it’s really just a question of “what’s the situation we’re looking at?” Are we actually talking about indigenous farming that was traditionally used as subsistence farming, but now the World Bank in the 70s started making them export? So there’s a lot of these political factors that are what actually make people upset—not the biology, but the politics and economics, but those things get conflated.

It’s interesting to think about, for example, regional cuisine and protected designation of origin foods in Europe. As climate change will shifts growing conditions, PDO plants will no longer grow [in their original locations]. Will people accept genetic modification as a way of continuing that tradition, or will that be completely unacceptable? I have a feeling, especially for something like a Bordeaux wine, it will be completely unacceptable. However, climate change may completley undermine the PDO system in Europe, which is grounded in the terroir of landscapes that go through changes from year to year, but are generally steady over longer time scales.

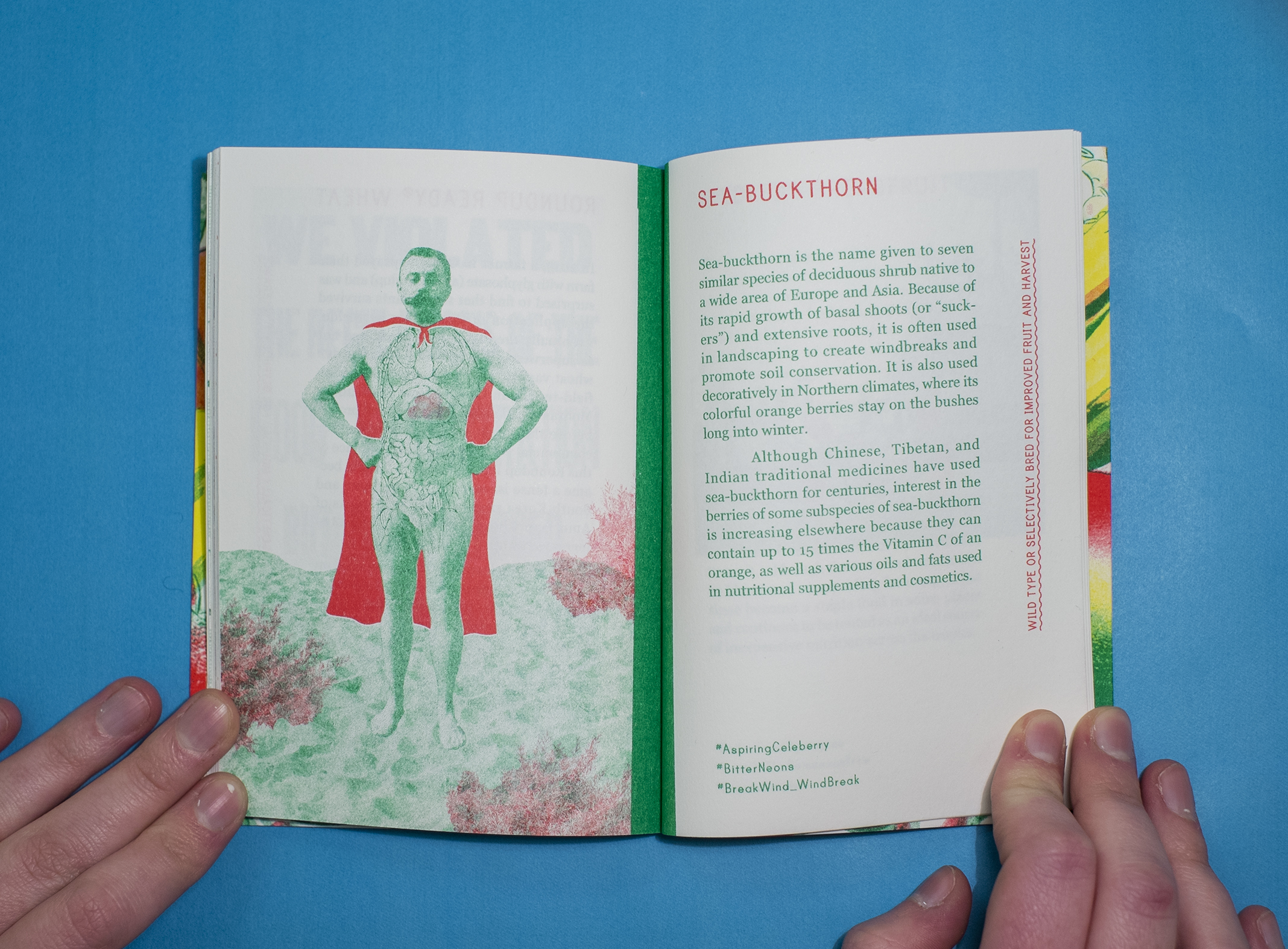

The Center’s Cobalt-60 Sauce

CGG: In our work, we do two things [that address this]:

One is remain critical in all aspects of the work. We’re not necessarily trying to be advocates, we’re trying to be critics about the politics, economics and biology. For example, we’re [currently] looking at the history of mutation breeding, but really it’s a prompt for our audience to go deeper into their biological fears, and to understand biology more, and say, “well what is the biological difference between transgenic technologies and mutagenic technologies?” In some ways, the mutagenic might be much more immeasurable in terms of its downstream effects and consequences for human and plant health. However, [transgenic and mutagenic technologies have very] different political contexts. The mutation breeding programs were state-run, top-down, centralized, whereas biotech, as it’s practiced in the US, is largely profit-maximizing, corporate-driven research. Mutation breeding was utopian and modernist, using new radiation technology to save the world and feed people. That’s some of the same rhetoric you see with GMOS, but both of those haven’t been successful at their stated goals. So there’s this hype and fear cycle, and at the end of it, you’re left with a new suite of crops and a new political configuration. And that’s what always happens—these technologies will never end starvation. [Starvation] is a political problem, it’s not a biological or even agricultural problem. So I think that’s why people are so disturbed and upset, because they see how much hype there was in the 90s with GMOs, how poorly it was delivered, and then the companies saying, “oh well it’s because you’re constraining us and putting more hurtles [in place].” But really, the whole conversation is moot, it’s not a biological [issue], it’s economic and political. So we’re trying to remain critical of this.

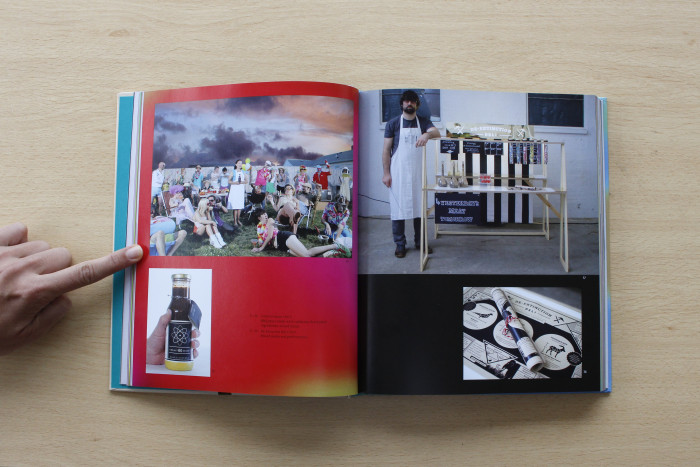

And then, since we actually serve food, we’re trying to give diners the opportunity to taste the future or to challenge themselves to put unusual things in their bodies, and that’s a very different commitment then what you see in Wired, CNN, or a lot of design fiction work, which is “here’s this crazy thing” and people don’t actually have to commit or remain critical because they just use their optics and not their physical or haptic ways of experiencing it. They see some crazy story on CNN about how steaks will be grown in the lab and we won’t have to kill animals, but they don’t have to actually deal with that process as it exists. When we do in vitro meat projects, like Art Meat Flesh, which is a cooking series where we cook fetal bovine calf serum, and say, “hey folks, right now, this is where the state of the art is. Are you comfortable eating this?” Some people are, and some people have left crying and throwing up.

Art Meat Flesh

S: What are the different types of activities that you do at the Center?

CGG: We do cookbooks, presentations, exhibitions, meals, lectures, and workshops. We’re a very small collective of artists so we’re very constrained by the funding that we can receive. We need to retain our critical voice, we don’t fall into the hype cycle of “in vitro meat will save everything,” but we also shouldn’t ignore that cultural narrative because we think it’s just hype.

We have to look for interesting and unusual outlets like arts organizations, DIY bio people, universities, but so far we haven’t worked with anyone like Frito-Lay or Coca Cola. I think the conversation we have is to make provocations, but to also ground our research in biology and ecology and to not just have paper architecture, or design fiction, or speculative fiction, which is basically 3D renders or special effects. Sometimes we will use speculative techniques when it’s appropriate, but we also have this desire to source actually ingredients so we can see the food system as it exists, as we imagine the future. We want to work with the organisms and ingredients themselves where possible.

S: So, in scenarios where you’re coming up with things that don’t yet exist, what’s your process for making that a visceral experience for someone?

CGG: They will often be really grounded in things that do exist- no future comes out of thin air.

With Mark Post, we made seven dishes, and one of them was asking, “Mark, if you could fantasize about combing any tissue culture or cells, what would it be?” He said, “In the US, they have ‘surf and turf,’ so it would be really cool to grow lobster cells and beef cells and combine them into a new thing.” So for that dinner in front of a live audience we cooked a live lobster, and cooked steak and put it in the blender with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and egg whites (the FBS was an amazing binder), and served it as a paté. So we were trying to communicate a few things: one, you can combine a few different cells in the lab and have this fantastical protein translation, but also that it’s going to be a mush. It’s not going to be a steak. So this idea of “realist speculative gastronomy” – they are actually eating this thing, they’re feeling the mushy flavor in their mouth, they’re getting the scent of iron. In this case it is a metaphor, it’s not actually meat grown in the lab, but it has a lot of the components and they also have to stomach it. We’re trying to create metaphors that don’t already exist in the dominant discourse around the future of food.

[Another] project is the Vegan Ortolan, where we took the cruelest meat dish we could find, and now have an ongoing cooking contest where people try to make a totally vegan version of it—[the chefs] have to make the bones, the liver, the head, the brain. So this is imagining, what if we didn’t have just fake sliced meat that was vegan? But actually recreate a whole animal? We’re actually talking about [this project] now as cultural exorcism. What people love about beasts is that there are many complex components, and that if we push that to its extreme, what does it look like? Political vegans don’t want fake meat, some vegetarians and less political vegans will have it, but what if we took this to an extreme that no one really wants? To recreate this really cool dish and exorcise these ghosts from the past of cruelty.

Vegan Ortolan

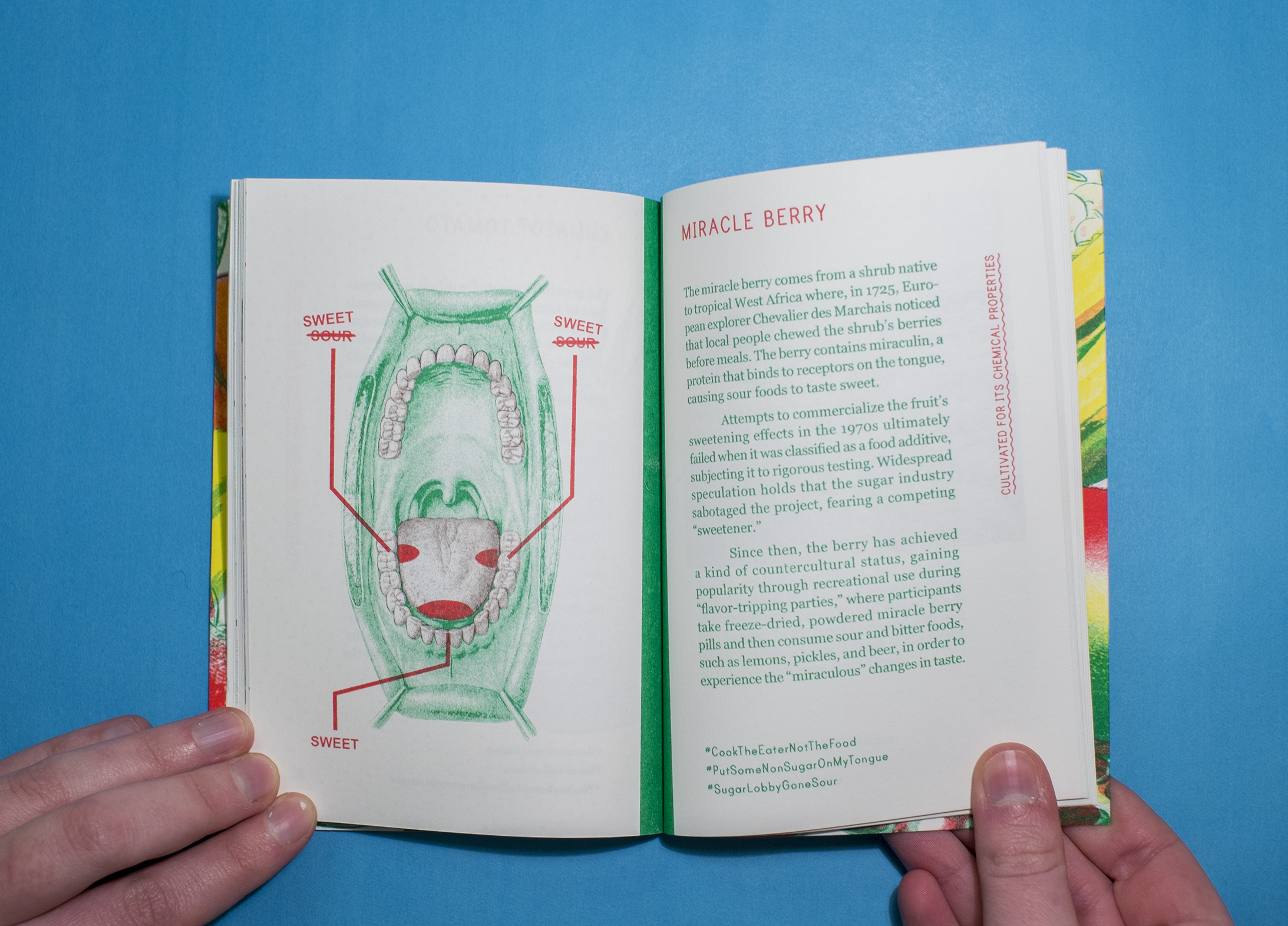

S: What did [Vegan Ortolan] look like? What’s its story?

CGG: Artists play with a lot of symbols. [Vegan Ortolan] is a symbol of a lot of things: high french cuisine, the ultimate dish of decadence, maleness and male kitchen culture. It’s illegal to sell in the EU, but it’s still served in back rooms, and it was Mitterrand’s last meal.

[The Ortolan bird] is force-fed, it’s eyes are poked out, you keep it in a box, then it’s drowned in armagnac. Then it’s baked in the oven for twenty minutes and you’re supposed to eat it whole, so you have the beak, the bones, the guts, and the idea is that all these flavors swirl together in your mouth and it takes a good while to chew.

Z: I think what a truly delicious vegetarian or vegan cuisine requires is human labor. Instead of the [responsibility] being put on the animal to put this biomass on its body and have this real complexity, vegetarian and vegan cuisines will demand human attention and care. They won’t be able to be industrialized, though maybe some components might be industrialized, but what’s going to make [them] amazing are those last moments where herbs, spices, combinations of flavors and textures put together by a chef. The US is particularly unsuited for this. We have such a hard time now with labor and paying humans appropriately because of exploitation, so we try to get in efficiencies through machining or making things really industrialized in chain kitchens. Vegan Ortolan is the opposite of that. It’s trying to take all these different aspects of an animal and the flavor profile, the crunchiness of the bones, the unctuousness of the flesh, the bitterness of the guts, the performance of it, that food should be an opportunity to celebrate or to tell a story. It’s really the anti-industrial food narrative, but wrapped up in this story that people are familiar with about cruelty to animals.

[This project] creates a moment of dissonance, disgust and often dark humor, which is really important for us. People ask, “Wait, what is their position? Why would you want to make a vegan thing about cruelty? That seems really weird… or why do they have sheets over their heads?” We want to deal with in vitro meat on its own terms sometimes, but also want to tell the story of the future of protein with totally different metaphors, and this is one of those metaphors. It’s not a normative one, so people actually have to stop, and think, or laugh, or be confused or process it. Whereas when you see a steak in a petri dish people are like, “oh yeah, I get it, that’s the future.”

PHOTO CREDIT: Luke Hayes

Decadence For All, Lisbon Planetary Sculpture Supper Club

CGG: We have an essay that we wrote called, “Decadence for All” [about how] this idea of decadence, or joy, or excess shouldn’t only include images of meat and rich people. How do we actually create decadence and excess in ways that are pleasurable? And not just over-consuming potato chips and soda (though there’s something to be said for that). So the Vegan Ortolan is part of that research base: how do we actually create a vegan dish that’s decadent and uses older metaphors and almost turns them on their head? That’s one aspect of it.

S: So would you say that one of your visions for the future of food would be “decadence for all”?

CGG: That would be a much better solution space than “efficiency” because it takes into account, beauty, and joy and pleasure and possibly sustainability (if it’s really for all), and inefficiency and resilience. Yes, I would rather see people making decadence and pleasurable food systems, than efficient.

S: What are you most hopeful about and most fearful about for in our future of food system?

CAT: I’m most hopeful for increased biodiversity, seeing small movements concerned with food taking off and becoming more mainstream. The fact that food has blown up as a topic over the last few years is really amazing.

Z: Culinary biodiversity, agricultural biodiversity. I’m most hopeful about the diversity of approaches and solutions and actors that are trying to solve interesting problems. Think tanks, corporations, chefs, farmers: the scale of people who are actively identifying food as a thing that needs lots of different voices is really exciting. I think I’m most scared of the Bay Area and tech entrepreneurs who don’t understand that food is not code. They have a lot to contribute, but until they that disruption has a downside, that could be a little bit scary. We’ll wait and see how it plays out.

S: So, speculate on two scenarios: one is that people are going to have it be genetically modified and still be from that place, like the terroir is still the most important thing. Or [two], they would rather not have modification, so what would the alternative seal of quality or cultural legacy be on a product?

Z: There could be a biological seal where people look on the genetic level.

C: So you would almost have to sequence the DNA to [know what it is].

Z: PCR to mouth.

S: Is it possible to fake those bio markers?

CGG: Sure, that’s the sort of the design noir approach: what’s a sort of emerging technology and how do we use it?

One way you can distinguish between good food and not-so-good food is through taste. But [changes] happen slowly over time. For example, tomatoes becoming less and less flavorful over time. You don’t really notice it from one day to the next. But within a decade there’s a huge shift that’s happened.

This is where Europe is going to have a lot of problems. Their food culture is still rooted in conservatism, whereas the US is so much about innovation. I think actually the US (I go back and forth on what opportunities different geographies have) has a great opportunity to do adaptive bioregionalism. It’s not as set in its ways. If we see plants migrating north because of warming, like maple trees and maple syrup [for example], bioregionalism isn’t set in stone. It needs to be adaptive, and so much of the new EU laws around food are codified, whereas the US is willing to innovate. So that combination of innovating and trying new things and the entrepreneurial spirit with a sensitivity to ecosystems and regionalism is actually a great place for the US to be in, but it would mean that food systems would have to decentralize, and Portland (or the Pacific Northwest) is one of the few examples of food systems that are really starting to do that.

C: I wonder if less weight will be given to geography as these things shift and change. So, it may not be about a PDO (protected designation of origin), it might be a PDA (protected designation of atmosphere), where you’re looking at air quality and humidity and other elements of the environment as opposed to a physical geography.

S: Dan Barbar is the Chef at Blue Hill in New York and he has a new book out called The Third Plate. [He writes] that if the first plate was the iconic American steak and potatoes (industrial farmed food), then the second plate would be a grass-fed beef with heirloom tomatoes and a farm to table movement, but dictated by the proportions and driven by high french cuisine ([yet still with] the whole American ethos of never being constrained and a total abundance)… [then] his vision for this third plate would be one that’s driven by the constraints. What would an actual American cuisine look like? A cuisine that is constricted by the actual resources available to us? So if farmers are having to grow heirloom tomatoes because that’s what chefs are demanding, then they’re also growing all these other things, like the beans they grow in between cycles to fix nitrogen into the fields, so that they can actually grow those tomatoes well. So, how can we embrace and actually support the full system?

CGG: The cuisine of permaculture or adaptive bioregionalism. I think that’s great. I think what’s exciting about the US as well, is that it’s open to the new technologies and techniques of food. So if there’s an absolutely amazing, high performing ingredient like Beyond Eggs that you can then combine with some other thing, people here will do that. They’re not afraid of that kind of thing. And that’s great, but it has to be a choice, and it has to be pleasurable and desirable. It can’t just be like, “oh you should never eat eggs because they’re naughty,” or “this is much cheaper, go with it.” It depends on the values and beliefs that you’re making these decisions based on, and if it’s about pleasure and joy, I’m all about combining the most crazy, industrial ingredient with a just-picked, wild herb. That’s the most exciting part! And those people are starting to talk to each other.

S: That’s a great metaphor to come away from here with, “how can we be cultivating pleasure and joy in everything we do?”

Image courtesy of MU

Image courtesy of MU